U.S. Government Propaganda Photo

By Ted Lipien

Almost no one knows today that one of the targets of misleading Soviet and American propaganda during World War II were Polish refugees fleeing from Russia. Before they were refugees, they were Stalin’s prisoners. The Red Army and the NKVD Soviet secret police occupied their cities, towns and villages in pre-war eastern Poland under the secret provisions of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact. Poland was attacked by Germany from the West on September 1, 1939 and by Russia in the East on September 17. It was the start of World War II launched by the two greatest mass murderers of the 20th century, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin.

September 1939, the arrests and deportations to the Soviet Gulag was only the beginning of the story of Polish refugees who at the end of the war had no homes to return to and no immediate hope for freedom in their own country even though Poland and many of them fought against Nazi Germany on the side of the winning powers. Their story, particularly the plight of Polish women and children who had survived the Soviet imprisonment and those who had not, deserves retelling, if only to understand better how propaganda was and is still being used today. When the tragic fate of Polish refugees from Russia was mentioned during the war in official communications, it was falsely presented and callously exploited by U.S. government propagandists, partly for the benefit of the refugees’ Soviet oppressors. It was excused then and later by some Roosevelt administration officials as made necessary by a total war with Nazi Germany and Japan. It was also met with criticism from many Americans even during the war.

Events that happened in the middle of the last century may now seem distant, but some of the history behind them is being repeated today with remarkable similarities. Very few Americans know that long before the current controversy over Russia’s propaganda interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Russian propagandists scored a major victory against the United States of unprecedented historical impact in a different technological age of transnational news media and propaganda operations. They turned Soviet crimes against humanity into proofs of struggle for peace and democracy against the forces of fascism–a reoccurring theme of Russian disinformation. They did it with active help from U.S. government officials and a few agents of influence in the progressive wartime administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, mostly in the Office of War Information (OWI) which was responsible during the war for both domestic and foreign propaganda.1 In the process, as a bipartisan congressional investigative committee concluded after the war, U.S. propagandists betrayed America’s principles and allies. Some of those betrayed were refugees from communism, including women and children who had lost their husbands and fathers in prisons and forced labor camps in Soviet Russia.2

Thousands of Polish children refugees, many of them orphans and some half-orphans in care of their mothers, presented a potentially big problem for the administration’s effort designed to sell Russia to Americans as a valuable war ally, which Russia clearly was at that time from a strictly military point of view. After over 100, 000 refugees were evacuated from Russia to Iran in 1942, their presence was a potential embarrassment for both Soviet and American officials. They were the first large group of witnesses from the Gulag who found their way to freedom and could tell their story.

The Polish refugees could damage the propaganda narrative created by the Roosevelt administration. Not satisfied with only military cooperation between the United States and Russia, American manipulators of public opinion were also trying to present the Soviet Union as a force for peace and democracy, and its demands for control of East-Central Europe as driven by legitimate security concerns. The story of the Polish children’s ordeal and a large number of orphans among them threatened to cast a shadow on Russia’s geopolitical demands and the idolized image of the Soviet dictator. Russian and U.S. government propagandists joined forces to censor, silence and, if all else failed, to distort the voices of Polish refugees. Even today, very few people know about Polish orphans miraculously saved and evacuated from Russia in the middle of the war. Theirs was not the story that pro-Soviet Roosevelt administration propagandists wanted Americans to know about. They did not think twice about locking the children up in a former detention camp for Japanese-Americans or transporting them in sealed trains guarded by U.S. Army soldiers to minimize any chance independent American reporters might get hold of the refugees and publish anything more than what they would get from using an OWI press release, which many of the reporters ended up doing.

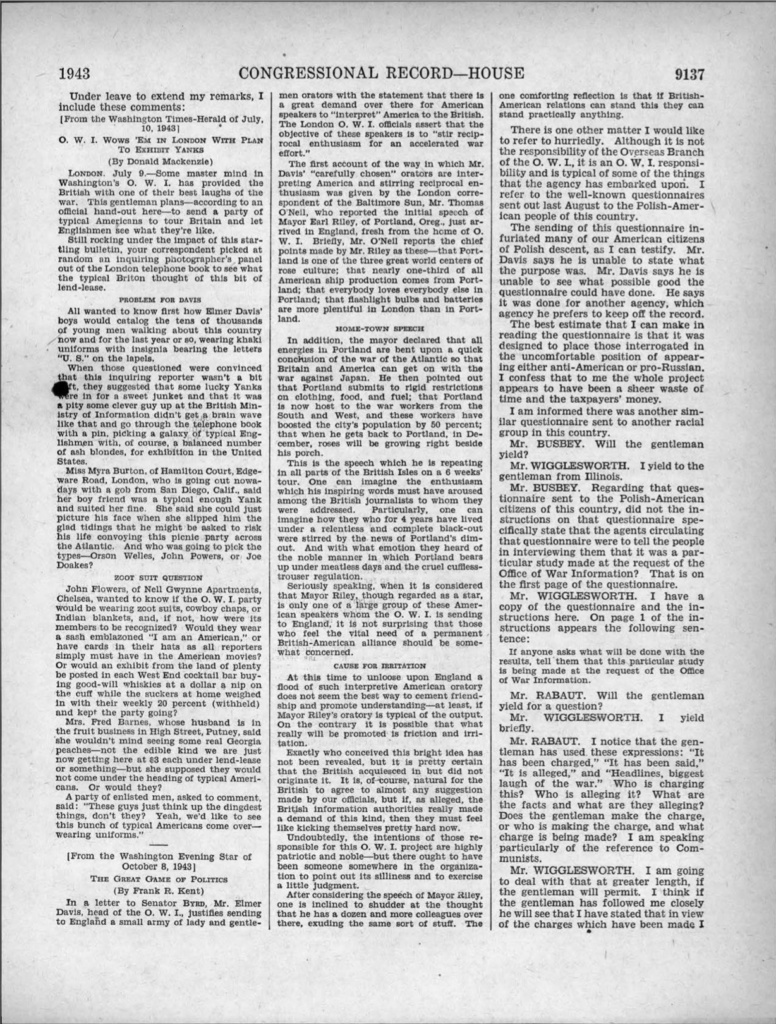

Manipulative aims of the Russian disinformation effort assisted by U. S. government employees at American taxpayers’ expense did not remain entirely unnoticed during the war, but not specifically in the case of refugees fleeing Russia. There were public and behind-the-scenes protests from both Democrats and Republicans concerned about communist and Soviet influence over OWI radio programs which became known as the Voice of America (VOA), but the Polish orphans were not mentioned in connection with any such criticism. Both the Russians and the Roosevelt administration succeeded in keeping Polish refugees from attracting wider media attention. What was sometimes mentioned in public already during the war, especially in the U.S. Congress, was the larger concern over growing Russian influence within the executive branch of the U.S. federal government. These concerns were vigorously challenged by the administration and its supporters even as some of the most active communists were being quietly removed from their government jobs in response to pressure from Congress. At one point during the war, angry and suspicious U.S. lawmakers substantially cut the funding for OWI’s domestic propaganda. After additional evidence of government propaganda abuses came to light later, the U.S. Congress passed the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act to severely restrict domestic distribution of news and information by the executive branch.3

Already during the war, key U.S. military leaders and diplomats, including Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles who was responsible for arranging U.S. government help in resettling some of the Polish refugee children, were secretly warning the Roosevelt White House about pro-Soviet propagandists employed in the Office of War Information. General Eisenhower accused them of “insubordination” and endangering the lives of American soldiers.4 There were articles critical of the Office of War Information in the New York Times and in more conservative newspapers, warning of U.S. government journalists becoming too cosy with the communist movement and the Soviets. A protest by American labor unions against pro-communist Voice of America broadcasts became public and was reported on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1943.5

It took the United States several decades, billions of dollars and the losses of American lives in the wars in Korea and Vietnam to undo the damage of by far the most successful Soviet disinformation offensive carried out in collusion with a number of American officials and U.S. government employees who were in charge American shortwave radio broadcasts and used them to spread Soviet disinformation abroad while at the same time targeting Americans at home with the same uncritical and dishonest pro-Soviet messages. This shameful example of journalists working for the U.S. government being deceived into spreading Russian disinformation and using censorship and other illegal means to mislead independent media has been now almost completely forgotten. It is not mentioned in reports about current political events and Russia’s information war against the United States although it should be viewed as highly relevant, offering lessons to be learned.

To this day Americans are still being given by government officials a different history of the Voice of America. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Amanda Bennett who is VOA’s current director appointed in 2016 during President Obama administration wrote in a November 27, 2018 Washington Post op-ed that “The radio broadcast that eventually became Voice of America was created to give people trapped behind Nazi lines accurate, truthful news about the war, in contrast with Nazi propaganda.” She added:

Those broadcasts were lifelines to millions. Even more important, however, was the promise made right from the start: “The news may be good for us. The news may be bad,” said announcer William Harlan Hale. “But we shall tell you the truth.”6

That was not what non-communist listeners discovered in American government radio broadcasts during World War II, although it became true somewhat later. Czesław Straszewicz, a Polish journalist based in London described the discouraging impact of VOA’s pro-Kremlin wartime messaging on the audience in Nazi-occupied Poland and among the free Poles abroad. When Stalin let the 1944 anti-Nazi Warsaw Uprising bleed to death, by refusing to provide assistance and not allowing American planes carrying supplies to land on the liberated territory just outside of the Polish capital, the Voice of America obliged him by ignoring the fighting Poles. Soviet propaganda dismissed the Warsaw Uprising as “foolish and futile” while VOA dismissed it with silence.7

With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.8

One of the several recipients of the 1953 Stalin International Peace Prize was American writer, journalist and Communist Party USA activist Howard Fast who ten years earlier had been the chief news writer for Voice of America radio broadcasts in the Overseas Division of the U.S. Office of War Information. After getting hired by OWI in December 1942, Fast was recruited early in 1943 to be the chief English news writer for the Voice of America radio programs to Europe. His primary patron was the first VOA director John Houseman who also hired many other Soviet sympathizers and Communist Party members to produce wartime VOA broadcasts.

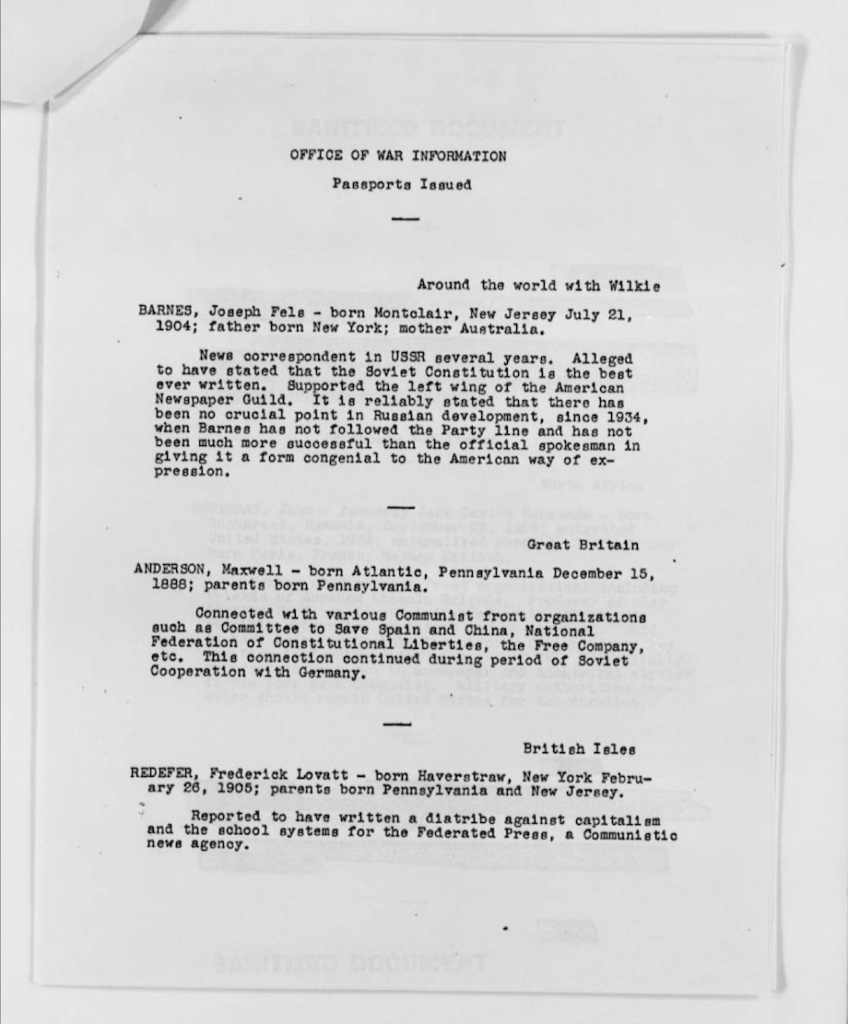

After becoming aware of the large number of Soviet agents of influence at the U.S. wartime propaganda agency, the State Department with the backing from the U.S. Army Intelligence and with approval from President Roosevelt’s close friend and foreign policy advisor, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, refused to give U.S. passports to both Howard Fast and John Houseman for their planned government travel to North Africa on VOA business in 1943. Both Houseman and Fast resigned form their positions with VOA. Houseman left in mid-1943. Fast left in early January 1944 and became a Communist Party activist and reporter for its newspaper The Daily Worker. In his 1990 memoir Being Red, Fast bragged that he got his news about Russia for Voice of America broadcasts from the Soviet Embassy and would not allow any “anti-Soviet propaganda,” which to him was any information critical of the Soviet Union.

The promise to tell the truth did not apply during the war to Soviet Russia, refugees from communism, millions of Stalin’s victims and almost any news pro-Soviet VOA officials and broadcasters thought would reflect poorly on the Soviet regime.

In fact, a secret OWI “Manual of Information” stated that while lies should be avoided, the whole truth does not always have to be told: “…information is not disseminated abroad merely because it is true–it must be useful in the psychological warfare program of the OWI, which is designed to shorten the war and thus save lives. The whole story may not always be told, but the story which is told will always be true.”9 As many found out, including refugees fleeing from the Soviet Union and the wives, mothers and other relatives of the Katyń victims, even such a limited promise was also not always true.

President Roosevelt and some of his advisors chose to ignore history. After the Soviet Union attacked eastern Poland on September 17, 1939 to fulfill its part of the bargain with Hitler, entire families were arrested, evicted from their homes and sent to prisons, forced labor camps or collective farms throughout the Soviet Union but mostly in Siberia and Central Asia. Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Tatars and other nationalities were also deported en mass on Stalin’s orders. The only reason the Polish prisoners were released by Stalin after less then two years was because Hitler betrayed him and launched an attack on Russia in June 1941. Being unsure at that point whether he would survive the German attack, Stalin was forced to make a temporary accommodation with the Polish government in exile to get help from the United States and Great Britain. As soon as the German threat receded, he reneged on his promises to the Western allies and to the Polish government in exile.

In 1942, about 120,000 Poles, only a small number of those who had been arrested and deported by the Soviets from eastern Poland in 1939 and 1940, were evacuated from Soviet Russia to Iran. The possibility of them talking to the media about their captivity became a sensitive issue for Soviet and American policy makers. Both governments took actions to obscure, minimize and counter any negative impact the plight of Polish refugees might have had on American public opinion. It was critical that Americans would not find out that in the spring of 1940 Stalin had ordered thousands of Polish military officers who were in of Soviet captivity to be shot in a series of secret executions known as the Katyń Forest massacre. Roosevelt administration officials knew about it from U.S. military intelligence reports but kept them classified to protect Stalin, ostensibly in order to keep Russia fighting Hitler and not to upset the U.S.-Soviet military alliance. In their ideological zeal, they also could not fanthom that Stalin could be a brutal dictator, but a report sent to Washington from Iran by a U.S. Army officer at the end 1942 and many other classified cables described various aspects of Stalin’s plans to exterminate Polish elites in eastern Poland through executions and deportations.

…it appears that the plan was very carefully worked out, and its purpose was the extermination of the so-called intelligentsia of Eastern Poland.

…Families were broken up and in many cases the husband shot.10

It is hard to tell who within the Roosevelt administration saw classified reports about Stalin’s atrocities, but both American and Russian propagandists tried to hide the news of crimes against humanity being committed by the Soviet communists from being discovered. OWI officials and VOA journalists quickly dismissed evidence of such Soviet crimes as false Nazi propaganda. Later on Soviet propagandists went much further and accused non-communist Poles of being right-wing reactionaries, anti-Semites, and fascists–not unlike some of the labels applied by the Kremlin’s propaganda outlets today to Ukrainians and others who oppose current Russian acts of aggression and intimidation. American propagandists were satisfied with merely censoring out information potentially damaging to the Soviet Union.

The Polish government in exile was also for a period of time contributing to the silencing of the story of Polish refugees. The Poles in charge of the government based in London were not eager at first to publicize widely what had happened to the former Polish prisoners in Russia although privately they were keeping U.S. and British government officials fully informed. Stalin was still holding thousands of other Polish citizens as hostages and was refusing requests to allow them to be evacuated to Iran. Some within the Polish government feared that too much publicity could endanger diplomatic efforts to get more of the former prisoners evacuated from Russia and to improve Polish-Soviet relations. In the end these efforts failed because Stalin had other plans for Poland after the war.

For propagandists in the Roosevelt administration, Polish refugees who fled from Russia in 1942 had to be presented as something else from what they were. Not as fascists, which became the Soviet propaganda theme, but as refugees fleeing Nazi aggression—a deceptive claim because they were not from the part of Poland occupied by Germany and were forcibly removed by the Soviets from their homes long before the Germans occupied the area in 1941. Their tragic fate was falsely presented and used by OWI and VOA to score propaganda points in favor of the Soviet Union in press releases and radio broadcasts. The Roosevelt administration would not allow the refugees to provide evidence of Stalin’s communist brutality, but extreme left-wing U.S. propagandists were in any case not inclined to believe in any charges of communist repression or eager to report them. They happily accepted and promoted Soviet propaganda in press releases and photographs sent out to the media, public exhibits, publications mailed out to millions of Americans, domestic radio talks by OWI director Elmer Davis, and Voice of America radio broadcasts beamed abroad.11 They also produced propaganda films justifying the illegal internment of Japanese-Americans loosely modeled, without the brutality and death, on Stalin’s deportations of various nationalities—the Poles being just one many such groups.12

Evidence of communist atrocities were available to journalists willing to ask questions and report on them. By visiting the hospitals in Teheran where some of the Polish refugees from Russia were still dying from the effects of their captivity, the Office of War Information could have used photographs to document the horrors of the Soviet Gulag, and the Voice of America could have reported on it. Instead, OWI took photographs which showed healthy refugees and U.S. government press releases carefully avoided mentioning what drove them to leave the Soviet Union.

A U.S. government propaganda photo taken in 1943 by the Office of War Information (OWI) photographer showed a healthy-looking Polish woman at a refugee camp in Iran. Other OWI photos showed smiling and well-nourished children. A few months earlier along with hundreds of thousands of other Poles, they were Stalin’s prisoners deprived of liberty, adequate food and medical care. Women had been forced to do hard labor to receive food rations for themselves and their children. Food was barely sufficient to survive. They lived a miserable existence in most primitive conditions. Women were raped or were driven into prostitution to feed themselves and their families. A classified U.S. military intelligence report described the dire situation of women prisoners in Stalin’s Russia.

The deportees were assigned work in coal and iron mines, on the laying of roads and railroads, on irrigation projects, in forests, on construction of building, on farms. No discrimination was shown between men and women. A woman had to cut and pile as much wood as a man, she had to carry 15 lbs. of bricks or mortar, she had to excavate 9 1/2 cubic meters twice-shifted despite the fact that the normal excavation was 6 cubic meters. … if anyone fell below the quota, he or she, was docked and consequently could not buy enough bread.13

Thousands of Poles, some of whom could have been relatives or friends of the woman in the OWI photograph, had already died from hunger and illnesses. Some of the fathers and husbands of the women had been executed by the NKVD secret police in what amounted to ethnic cleansing and genocide of the Polish intelligentsia from the eastern part of Poland.

Roosevelt administration officials in Washington were getting reports from their diplomats and military sources who knew what was done to Polish prisoners in Russia, but such reports were immediately classified as secret and some were later destroyed.

In 1942, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt received translations of several letters written by Polish refugee women begging for help in finding their husbands still missing in the Soviet Union. The letters were sent to her by Helena Sikorska, the wife of Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski, with an urgent plea for her intervention. This correspondence was also classified as secret. Even Helena Sikorska asked for it to be kept confidential in order not to embarrass the Russians or harm the anti-German alliance. There was no record of Eleanor Roosevelt taking any action other than passing the letters to the State Department which already knew about them. In any case, the missing Polish officers were already dead. More than 15,000 (over 20,000 if other members of the Polish intelligentsia are included) were executed two years earlier by the NKVD secret police on the orders of Stalin and the Politburo. They were bound, blindfolded and shot in the back of their heads in Katyń and at several other locations.14Helena Sikorska, whose husband died in a mysterious plane crash in 1943, published in 1946 accounts of many Polish men and women, former prisoners in the Soviet Gulag, in a book titled The Dark Side of the Moon with a preface by T. S. Eliot.15

Stalin had an army of willing communist executioners, but one significant finding in various classified U.S. government reports was that not all Russians were brutal and corrupted by the communist regime. A Polish woman told a U.S. Army officer that relations between Polish and Russian prisoners were good. Russians were also victimized by Stalin’s NKVD. A few years later great Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn became himself one of the millions of Russians who were arrested, convicted of anti-Soviet activities and forced to work in the Gulag. In his poem, “Prussian Nights,” the Nobel Prize-winning author described the gang-rape of a Polish woman whom the Red Army soldiers mistakenly thought to be a German. It was a common fate of millions of German women, but also Polish, Jewish and women of other nationalities who came in contact with soldiers of the Red Army at the end of World War II. It was another news that the Voice of America and most other journalists failed to report.16 Soviet propagandists, with some help from quite a few Western journalists, would later portray Solzhenitsyn as a nationalist and a Nazi sympathizer. He was neither, and neither were the Poles in Iran who had escaped from the Soviet Union and remained loyal to their legal and democratic government in London.

The U.S. Army colonel who wrote a report with accounts about life in Soviet captivity shared with him by Polish women was Henry I. Szymanski, who served as an American liaison officer to the Polish Army. He worked closely with Polish Army officer Captain Józef Czapski who himself barely escaped the Katyń Forest executions. Both Czapski and Solzhenitsyn were targets of temporary censorship by Voice of America at different times even during the Cold War when some reporting on Stalinist atrocities was already allowed but most graphic accounts were still censored. While not ideologically driven and as complete and as deceptive as during the Roosevelt administration, the later partial censorship of the Katyń story at the Voice of America happened under the Republican administrations of President Nixon and President Ford. It was roundly condemned by both Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. Congress. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty successfully resisted such censorship.

During the wartime military alliance between the United States and Russia, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty did not yet exist. At that time, witnesses of Soviet genocide had absolutely no chance of having their interviews broadcast by the Voice of America or be mentioned in any of the Office of War Information publications. A near total silence about them was enforced. In contrast, at the end of the war, U.S. government photographers and filmmakers extensively documented Nazi crimes at the liberated concentration camps in Germany. While far from being the only reason, unwillingness to collect evidence and prosecute communist war and post-war criminals meant that Americans and the world know now much more about Nazi-perpetrated genocide than about crimes against humanity committed by the Soviets and the communist regimes in East-Central Europe.

In a further insult to Stalin’s victims, the Voice of America’s management kept censoring some Gulag-related news reports even long after the end of the war. Czapski’s interview was censored in 1950 and readings from Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago were curtailed in VOA’s Russian Service programs for several years in the 1970s. This was not full censorship as during World War II and it ended when Ronald Reagan became U.S. president and called the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” Fortunately, even before the Reagan presidency, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty broadcasts were never censored to protect the Soviet Union from criticism. Despite some temporary setbacks, many Americans within and outside of the U.S. government, including VOA, RFE and RL emigre journalists and their American managers, worked diligently during the Cold War to undo the results of the Yalta betrayal and helped to bring about the fall of the Soviet Union and communist dictatorships in East Central Europe.17

The real story of the Polish woman in the OWI photograph, however, could not be told by OWI and VOA journalists during World War II. Even if they could, many of them would not want to tell her story because they unquestionably accepted Soviet lies. The Polish woman in the photograph was not the same woman who spoke with the U.S. Army officer. Lt. Col. Szymanski described his informant for “Case Studies–Polish Evacuees in Tehran” as a mother of five children. She was obviously older than the woman in the OWI propaganda photo which was taken the following year. The secret report on Polish-Russian relations dated November 22, 1942 presented testimonies of several Polish refugees in addition to the mother of five children whose husband was arrested.

THIRD INFORMANT

After her husband was arrested she was deported from Pinsk on 20.4.41. Was deported from hospital with 5 children. She was in hospital after the birth of her youngest child. The other children 17, 14, 8, 3, and 2 months [sic.] old. The whole family was transported to Semipalatynsk in cattle train. They were deported to the Camp of Semipalatynskaja Oblast, Bialagaczewskij Rejon, Bek-Kazjer, and there had to work in a quarry. Was released from work there as unfit, but her sons aged 17 and 14 were forced to work. The work consisted of carrying and loading blocks of stones from 7 in the morning to 4 in the afternoon. The salary was 11 kopek for one cubic meter of stones and both the boys could hardly load one cubic meter during one day. The loading of stones was often carried out during the night. They used to earn 11 kopek daily but the daily expenses for bread were of 5 roubles 25 kopek. We had separate lodging consisting of one room with a floor, a kitchen stove, one window 2 and half mtr. x 2 and a half mtr. The children were ill, malaria and scarlet fever. The local authorities of the quarry and the guards were severe but did not ill-treat the workers. Relations between Polish and Russian prisoners were good. After long efforts made by the deported they were released by the Soviet authorities on 27 October 1941 and received amnesty certificates. She left immediately afterwards for Farabu, where she stayed 2 weeks, afterwards left for Dzambul, Teren Uziuk. There her youngest child died, her daughter was seriously ill and became deaf.18

Women not accustomed to hard manual labor and consequently not able to earn enough for their daily bread had a choice of starving to death or submitting to the Bolshevik or Mongol supervisor. In one sense their condition was bettered–they had something to eat. When asked by me whether they worked hard, a reluctant answer of, “I wanted to live,” would be given [to] me. The Polish military medical authorities are taking blood tests to determine the number of venereals among women. The tests were not completed prior to my departure, but the results will be handed [to] me.19

Lt. Col. Szymanski took his own photos of starved, ill and dying Polish children as they came out of the Soviet Union in 1942. Both his reports and his photographs were also classified as secret and were not seen until 1952. Had they been made public earlier, they could have helped U.S. policy makers and other Americans make up their minds about Stalin without the corruptive effect of Soviet propaganda reinforced by their own government’s censorship and disinformation. Americans and foreign audiences were deprived of critical information about Russia.

Photo by Lt. Col. Szymanski, U.S. Army.

Photo by Lt. Col. Szymanski, U.S. Army.

Photo by Lt. Col. Szymanski, U.S. Army.

Photo by Lt. Col. Szymanski, U.S. Army.

The children had no chance. It is estimated that 50% have already died from malnutrition. The other 50% will die unless evacuated to a land where American help can reach them. A visit to any of the hospitals in Teheran will testify to this statement. They are filled with children and adults who would be better off not to have survived the ordeal.20

Lt. Col. Szymanski’s photographs should have been shown together with OWI photographs which were taken a year later after the refugees have recovered somewhat from their earlier ordeal. Hundreds still died in Iranian hospitals. News stories should have been written about how Polish refugees in Iran were transforming their lives while still coping with the effects and psychological trauma of their former imprisonment. At that time many refugees still did not know what happened to their husbands, fathers, mothers, children and other family members from whom they were separated during arrests by the Soviet secret police, while being transported in cattle trains to the labor camps, or afterwards. Their missing family members and friends were either already dead or languishing somewhere in Russia. OWI censors and propagandists tried to make sure that such stories would not be written and Americans and foreign public opinion would remain unaware of the key facts. In some cases, they used deliberate deception to mislead Americans and radio listeners abroad.

When the OWI photographs were taken in 1943, Polish women in Iran had a good reason to be happy about at least a partial reversal of their misfortune, even if some still did not know what had happened to their husbands, fathers, children, relatives and friends. They were the lucky survivors of the Soviet Gulag. The young woman seen smiling for the U.S. government photographer was finally free and under the care of Polish, British, and American authorities, as well as being warmly welcomed by the Iranians who were wondering why there were so many orphans among the Polish refugees. There were also many widows.

What the OWI photographs did not convey was the woman’s dark past in the absence of appropriate explanations, which the Office of War Information and its Voice of America radio broadcasts in English and foreign languages failed to provide in connection with the Polish refugees’ story. (VOA did not broadcast in Russian or Ukrainian during the war in order not to offend Stalin.)

The photograph’s official description, as preserved in the Library of Congress, did not mention that the woman came to Iran after being imprisoned in Russia. There was no reference to the Soviet Union in the caption. She could have been easily confused by Americans for being a lucky Polish refugee who had escaped from under the Nazi occupation thanks to generous assistance from the Soviet Union. That is what OWI officials and journalists wanted Americans to believe and that is how these Polish refugees were also presented in Soviet propaganda, which before and after condemned them for being ungrateful for the “help” they had received from Russia.

When some of the refugees tried to correct such disinformation, the Soviets immediately accused them of being anti-Soviet and fascist. In fact, Polish soldiers who had been Stalin’s prisoners joined the Polish Army of General Władysław Anders and fought the Germans alongside American, British and other allied troops in North Africa and Italy. After the war, they could not return to communist-ruled Poland where a few of those who had returned faced reprisals from the Soviet-dominated regime. Besides, they had no homes to return to. Their cities, towns and villages were in eastern Poland which was given to Russia with President Roosevelt’s acquiesce and without the knowledge and approval of the Polish government in exile. While the Red Army had occupied the region and could not be forced to leave short of war, President Roosevelt could have tried to extract concessions from Stalin which would have been more than empty promises. He could have also avoided damaging America’s reputation, which he did by betraying allies behind their backs.

U.S. propaganda made FDR’s betrayal of Poland even more obvious and more painful. When taken out of the context of the Polish refugees’ previous Soviet captivity, some of the U.S. Office of War Information photographs were indeed stunning and deserving of attention. They showed proud and resilient people. They also documented positive results of the assistance the refugees had received from the U.S. government, the American Red Cross and Polish-American institutions. Some of the refugees were wearing clothes sent to them by Polish-Americans.

The OWI photographs of Polish refugees in Iran were, however, in the purpose for which they were used, ultimately dishonest and deceptive. The OWI was a powerful U.S. government agency which carried out domestic propaganda as well as propaganda abroad through its Voice of America radio broadcasts. The man now known as the first VOA director, future Hollywood actor John Houseman, hired his communist friends and became unacceptable even to the Roosevelt administration.21 He was forced to resign, but many other Soviet sympathizers remained in their positions for the duration of the war.

A Polish-American newspaper Nowy Świat (“New World”), a target of an illegal and ultimately unsuccessful Office of War Information attempt to shut it down, published an editorial on January 4, 1944 which was discussed in a previously classified OWI memorandum. Nowy Świat commented on how the Office of War Information presented the story of Polish refugees in a press release sent out to U.S. media. The Polish-American newspaper pointed out that “the OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear.” In an earlier editorial, the paper had dismissed the OWI’s acceptance and promotion of the Soviet Katyń propaganda lie as “the sweat pills from the OWI pharmacy.” The paper wrote that it refused to accept the OWI’s news item on the Katyń Massacre because “we do not trust some of the alchemists employed by the OWI.”22 Some members of Congress often quoted from Polish-American media to expose Soviet atrocities and misleading pro-Soviet propaganda from the Roosevelt administration.

We are submitting this OWI article to our Polish readers as an example of the service Polish press receives from the Office of War Information. The observations of the American soldier on duty at Santa Anita, where Polish refugees en route to Mexico were housed, excited all. That is true. But the OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear. Freedom of fear… Polish children did not know of that freedom upon their arrival to America. But it also appears that neither does the OWI know of this freedom. It is afraid to admit that these children reached America from Russia. It speaks of a four-year journey, which they completed fleeing Hitler.23

A careless reader may gain the impression that with the beginning of the war, some group of Poles started on their journey to America, and after four years, had reached this continent. Not a word about the fact that together with millions of Polish citizens this group of refugees which has now reached Mexico was deported from Poland by the Soviets and was kept by Russia under the most miserable conditions. But seeing the obvious is not a virtue with the OWI. That Office is not evidently free from fear. (Fear) before whom?24

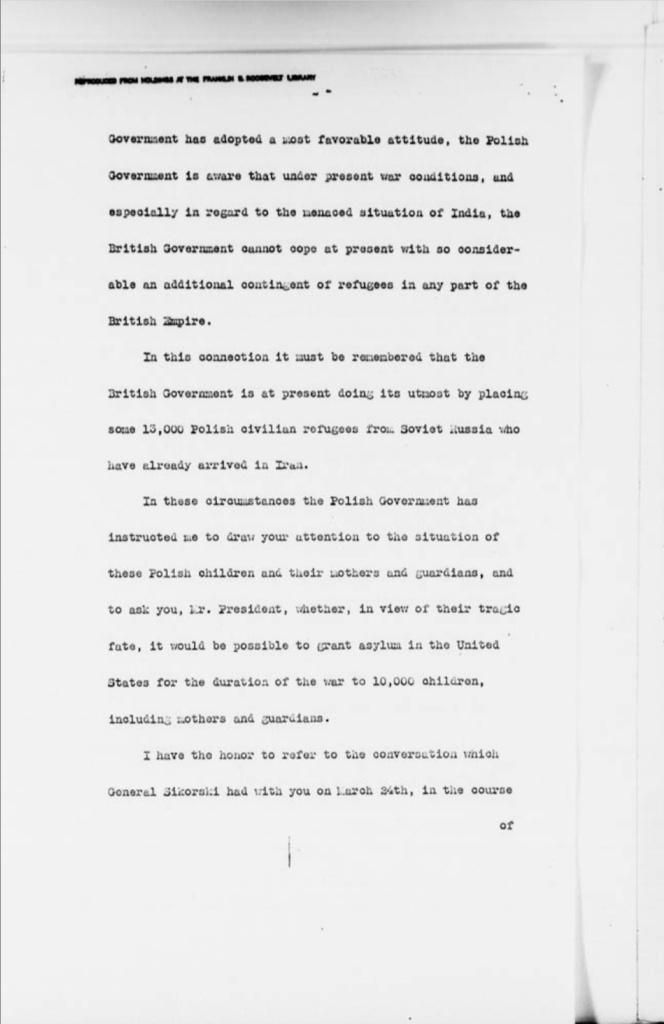

Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles had a more sober view of Russia than President Roosevelt, some of his other advisors, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Welles was instrumental in arranging for bringing a group of nearly 1,500 Polish children from India to be housed for the duration of the war in a refugee camp in Mexico called Colonia Santa Rosa.

Welles was also one of several prominent liberal Americans who had become concerned about Soviet influence at the U.S. propaganda agency. At the same time, he did not argue for the Polish children to be resettled in the United States. He probably knew that President Roosevelt would not agree to anything that could risk bad publicity for Stalin. He told the President that U.S. sea transport for a large group of refugees would be impossible to arrange. 25 As it turned out, it was not impossible to use a U.S. Navy ship in 1943 to make two voyages from India to California with Polish children on board, but even bringing the children to Mexico with a brief stopover in California carried some public relations risks, which administration officials tried to minimize with the help from OWI.

While Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles was genuinely trying to help the Polish government in exile with the refugee crisis and in other matters within the constraints imposed on him by President Roosevelt, knowing how FDR felt about his ability to handle the Soviet leader, whom he endearingly called “Uncle Joe,” there was no desire within the administration to use greater pressure on Stalin, certainly not by making the Polish refugee story public.

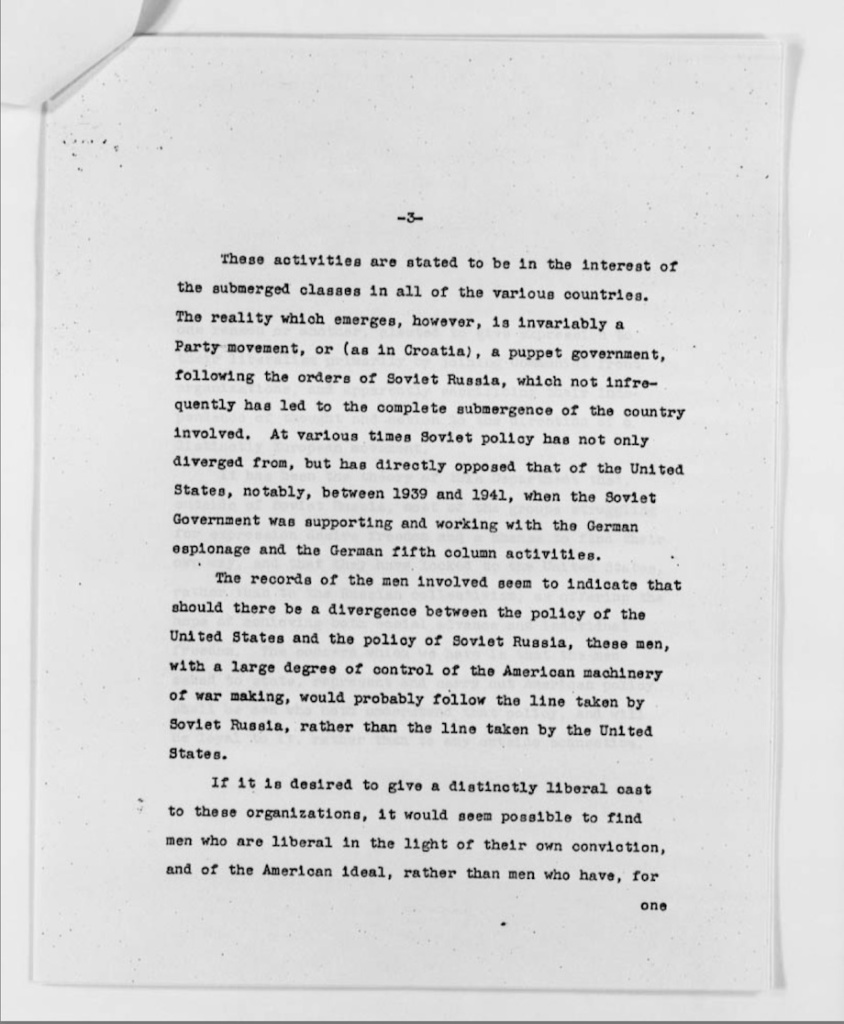

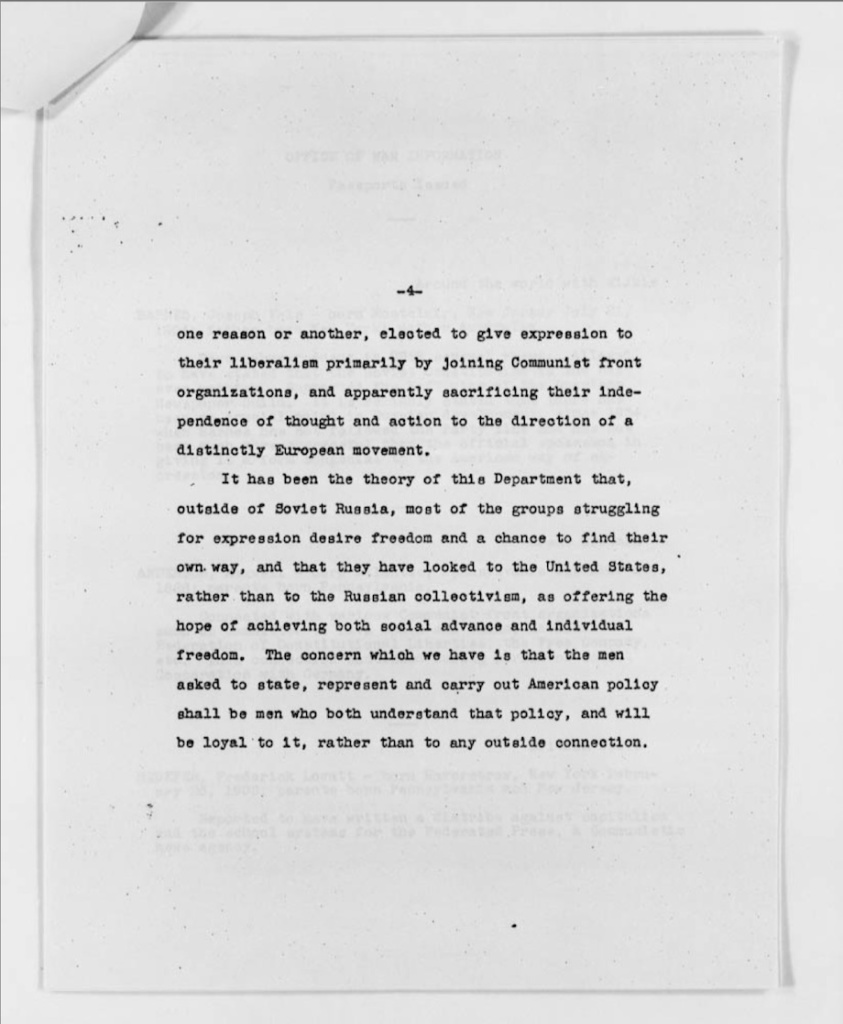

At the same time Welles quietly tried to reduce Soviet influence within the administration, particularly in the Office of War Information. In exposing John Houseman and several other Soviet sympathizers to the White House in a secret 1943 memo, Roosevelt’s personal friend and foreign policy advisor pointed out that Americans could be liberal without becoming communists and serving the interests of the Soviet Union.26

Despite the behind-the-scenes attempt by Welles and others to reduce Soviet influence and to bring U.S. propaganda more in line with U.S. interests, many communist and Soviet sympathizers kept their jobs in the Office of War Information.27 One of them, President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, Hollywood playwright Robert E. Sherwood, who became director of OWI’s Overseas Branch within which the Voice of America operated, was one of the most enthusiastic promoters of blending American and Soviet propaganda. According to one of Sherwood’s “propaganda directives” to the Voice of America staff, dated May 1, 1943, which instructed VOA broadcasters to accept what became the Katyń lie, the Poles who refused to treat as true Soviet propaganda on the mass murder of thousands of their prisoners of war in Russia were guilty of “consciously or unconsciously cooperating with Hitler.”28

Robert E. Sherwood’s propaganda directive callously dismissed the Polish government’s attempts to establish who was behind the murder of thousands of its military officers as typical of European nations emphasizing their “periods of martyrdom.” According to Sherwood, VOA broadcasters were to “Try to make America seem such a mighty world force that it will replace in the mind of the Poles Russia as an object of fear.”

In other propaganda materials, OWI was encouraging Poles to develop a friendly attitude toward Stalin and to trust in his good intentions. U.S. propaganda experts printed a small booklet with texts of two speeches by Vice President Henry A. Wallace translated into Polish. A copy of the booklet was found among the papers of a graphic artist who during the war was stationed at the OWI field office in Cairo, Egypt, which would suggest that it might have been produced for the soldiers of the Polish Army fighting the Germans in North Africa and for Polish civilians, some of whom were at refugee camps in the Middle East. Showing a remarkable naivety about the attitudes of the Poles who recently had gone through the hell of the Soviet Gulag, American government propagandists chose to translate a speech delivered by Vice President Wallace in New York on the 25th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, in which he said that “Today both Russia and the United States are seeking similar goals: both states are striving for the education, the productivity, and the enduring happiness of the common man.”29The idea that Stalin’s former prisoners could be persuaded that Stalin and communist Russia were changing their course and moving toward some type of popular democracy showed supreme ignorance on the part of OWI propagandists.

It was hardly surprising that ideologically blinded OWI and VOA propaganda specialists would try to hide and distort the Katyń Massacre story, the Polish children refugees story, and in the process undermine the allied Polish government of Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski while professing support for the London Poles. According to Sumner Welles, the Soviet regime and its supporters abroad also worked against General Mikhailovich in Yugoslavia, the British government in India, which incidentally hosted a group of Polish children refugees, General Franco government in Spain and against the possible survival of the Baltic Republics.30 The New York Times correspondent Arthur Krock wrote in a report published July 31, 1943 that view of OWI writers have been “closer to the Moscow than the Washington-London line.”31

The labor federations AFL and CIO and members of Congress of both parties were still warning the Roosevelt administration at the end of 1943 about the subversive influence of communists within the Office of War Information and its radio broadcasting division. Several such warnings were made on the floor of the House of Representatives on November 4, 1943. Congressman Wigglesworth said that “material broadcast overseas by the O.W.I. at taxpayer’s expense has been sheer communism.” He revealed that some of the OWI employees already investigated and removed as a result of congressional inquires included “a former Vienna communist,…a former contributor to the Daily Worker and other communist front organizations, a Hungarian Communist, a German Communist.” He added that “a notorious Polish Communist” working for the OWI and “a Soviet agent who worked for the Soviet[s] in the Baltic’s, said to have forged press credentials,” have not yet been investigated.32

Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, one of the key individuals in charge of what became OWI’s future VOA Polish broadcasts, was a Communist who later became an anti-American propagandists and a denier of Stalin’s crimes for the Soviet-dominated regime in Warsaw.33 He vigorously denied for many years Soviet responsibility for the Katyń Forest massacre. Even in the early 1950s, a communist agent Zbigniew Brydlak had managed to infiltrate the Polish section of VOA’s European Bureau in Munich. Former VOA Polish Service deputy director Marek Walicki wrote in his memoir that after being uncovered and fired by American officials in charge of security, Brydlak escaped back to Poland and wrote articles attacking VOA and Radio Free Europe. This was at the time when the Voice of America already stopped covering up the Katyń Massacre and started to counter in earnest communist propaganda. Brydlak’s mission was to derail such reforms.34

The American delusion about Stalin lasted several years, but it did not become a permanent U.S. policy course. It was never shared by all Americans. Eventually, the voices of some of the refugees started to be heard along with news reports of new communist atrocities being committed behind the Iron Curtain. Some of the refugees who were journalists, broadcasters and writers were hired to work for VOA and replaced the former pro-Soviet staff. To reverse the propaganda damage of the pro-Soviet policies of the Roosevelt administration and the early Voice of America broadcasts, the U.S. government created in the early 1950s Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Only then, the whole truth about the Katyń Forest massacre, in which husbands and fathers of many of the Polish refugees were brutally executed by the Soviets and for which early VOA broadcasters blamed the Germans in line with Soviet propaganda lies, could finally be told to audiences in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union. But in the West, the story of Polish refugees from Soviet Russia never truly emerged in mainstream media. It was largely forgotten later in the Cold War as newer human rights violations were being reported. The first refugees from Soviet communism and the first witnesses from the Gulag were effectively silenced for many decades.

Truth is the first casualty in war, a journalist and Catholic relief worker Eileen Egan observed about how the U.S government treated the news of Stalinist atrocities the Polish refugees brought with them from the Soviet Union and tried to keep them away from independent reporters. She had worked with Polish children refugees who were sent to Mexico in 1943. She reported that “At the border crossing between the United States and Mexico, soldiers with bayonets had been placed on guard duty so that the refugees could not leave the carriages to mingle with American citizens.” These were American soldiers. On the Mexican side, the refugees received a warm welcome.35

During World War II, pro-Soviet officials in the Roosevelt administration saw friendship with communist Russia as an all important U.S. military, foreign policy and propaganda goal. Preserving a positive image of the Soviet Union was about protecting Stalin. It was also about making sure he would not reach a separate peace agreement with Germany and become again Hitler’s ally, even though chances of it happening in 1943 were practically non-existent.

In her human resources, Russia was definitely the strongest ally against Hitler, but Stalin was not doing America any favors out of the goodness of his heart or support for democracy. He was fighting for his own life and the survival of his communist dictatorship. He succeeded using weaponry supplied by the United States, without which the Soviet Union would have been most likely defeated by Nazi Germany in World War II.

A German victory over Russia would be an unimaginable tragedy and a major setback for the United States and Great Britain, but by 1943 in the face of German defeats there was no compelling reason for President Roosevelt to betray Poland and other smaller allies and to make decisions about the fate of millions of their citizens behind their backs. Roosevelt abandoned them in favor of Russia under the influence of his advisors in a naive belief that Stalin would help America secure peace and democracy after the war. Russian propaganda and agents of influence, including those working for his administration, made sure that Stalin’s interests were protected and advanced. They cared much less about Polish children and other refugees, including Jewish refugees, whose plight, according to American historian Holly Cowan Shulman, was also largely ignored by the Voice of America.36 Criticism from other Americans was not enough to stop President Roosevelt’s appeasement of Stalin, but it is important to remember that not all Americans shared FDR’s optimism and his rosy view of the Soviet Union.

The OWI photographs of Polish refugees in Iran were part of a larger disinformation effort by pro-Soviet Roosevelt administration propagandists in favor of Stalin’s Russia. In press releases to U.S. media, OWI tried to mislead Americans into believing that these Polish refugees were fleeing from Hitler, even though they came from the part of Poland occupied in 1939 by the Red Army under the secret provisions of the Hitler-Stalin Pact and were deported from their homes by the Soviet regime. That in itself should have been a sufficient warning for President Roosevelt and his propaganda team dominated by pro-Soviet officials, but instead they censored news unfavorable to Russia from U.S. government press releases for domestic consumption and from OWI’s Voice of America shortwave broadcasts for radio audiences abroad. U.S. propagandists wanted to protect Stalin from bad publicity without regard for the truth and America’s long-term international reputation.

Piotr Piwowarczyk, a journalist and film producer who lives in Mexico, described the brief journey of Polish refugee children through California during World War II as “surreal.”

“Having gained their freedom, the refugees arrived in America, a place that in their minds was freedom itself. But to their utter amazement, as they got off the ship, they were immediately put on military trucks and taken to a nearby internment camp holding Japanese Americans. [By that time Japanese Americans were most likely no longer there having been been placed earlier in permanent internment camps.] The Poles noted with misgivings that their own section of ‘Santa Anita’ was enclosed by barbed wire. They felt like prisoners again. Better conditions than in the Soviet Union but certainly not the America of their dreams. After four days, they were loaded onto military trucks again and taken to a train under military guard that remained posted at every door throughout their journey of some seven hours. The windows remained sealed, and no one was permitted to leave their coaches.”37

Even the Polish government in exile, eager to mend its relations with Moscow, discouraged the refugees from speaking about their experiences in Russia. There was pressure on them from all sides to remain silent. One of the children-refugees, Teresa Sokołowska, said many years later that they were condemned to be forgotten.

“Nobody spoke or wrote about our fate. After the end of the Second World War, we were a group lost in history.”38

When unable to completely ignore Polish refugees fleeing Russia , OWI propagandists tried to present them falsely as escaping from being under Nazi terror. Roosevelt administration officials even resorted to briefly keeping Polish children refugees, some of them orphans, under military guard in a former detention facility for Japanese-Americans and transported them to Mexico in sealed trains to prevent the real story of their captivity in Russia from reaching the American media. These were comfortable passenger trains and American soldiers were friendly, but some of the young children were traumatized because it remained them of being prisoners and their forced journey in crowded cattle trains to Siberia.

Time magazine and other American news publications were easily duped by Office of War Information propaganda. Their reporting was vague but strongly implied that the Polish children were fleeing from Hitler. Not a word was said in these media reports about their captivity in the Soviet Union and the circumstances under which they had become orphans. When it came to discussing Soviet communist terror, there was a deafening silence among OWI and VOA propagandists and many extreme left-wing American journalists.39

Ted Lipien is a journalist, writer and press freedom advocate. He is a former Voice of America acting associate director. During his career as a VOA broadcaster, reporter and manager, he was in charge of the Polish Service, Eurasia Division director and director of Eurasia Marketing Office in Munich, Germany and Prague, Czech Republic. He is the author of “Wojtyla’ s Women: How They Shaped the Life of Pope John Paul II and Changed the Catholic Church,” O-Books, UK (2008).

Photo Credits

U.S. Government Propaganda Photos

- Title: Teheran, Iran. Young Polish girl

- Creator(s): Parrino, Nick, photographer, Office of War Information (OWI)

- Date Created/Published: 1943.

- Link

- Title: Teheran, Iran. Women making their own clothing at a Polish evacuee camp operated by the Red Cross

- Creator(s): Parrino, Nick, photographer, Office of War Information (OWI)

- Date Created/Published: 1943.

- Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

- Link

- Title: Teheran, Iran. Polish faces

- Creator(s): Parrino, Nick, photographer, Office of War Information, OWI

- Date Created/Published: 1943.

- Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

- Link

- Title: Teheran, Iran. Women doing their laundry in a Polish evacuee camp operated by the Red Cross

- Creator(s): Parrino, Nick, photographer

- Date Created/Published: 1943.

- Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

- Link

- Title: Teheran, Iran. Polish woman and her grandchildren shown in an American Red Cross evacuation camp as they await evacuation to new homes

- Creator(s): Parrino, Nick, photographer

- Date Created/Published: 1943.

- Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

- Link

Photos by Lt. Col. Henry Szymanski, U.S. Army

- Twelve-year-old boy, Polish evacuee from Russia, August 1942

- Photos by: Lieutenant Colonel Henry I. Szymanski, U.S. Army

- Source: The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre; Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.); March 13 and 14, 1952 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), pp. 459-461.

Link

- Six-year-old boy, Polish evacuee from Russia, August 1942

- Photos by: Lieutenant Colonel Henry I. Szymanski, U.S. Army

- Source: The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre; Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.); March 13 and 14, 1952 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), pp. 459-461.

- Link

- Three sisters, ages 7, 8, and 9, Polish evacuees from Russia, August 1942

- Photos by: Lieutenant Colonel Henry I. Szymanski, U.S. Army

- Source: The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre; Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.); March 13 and 14, 1952 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), pp. 459-461.

- Link

- Ten-year-old girl, Polish evacuee from Russia, August 1942

- Photos by: Lieutenant Colonel Henry I. Szymanski, U.S. Army

- Source: The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre; Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.); March 13 and 14, 1952 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), pp. 459-461.

- Link

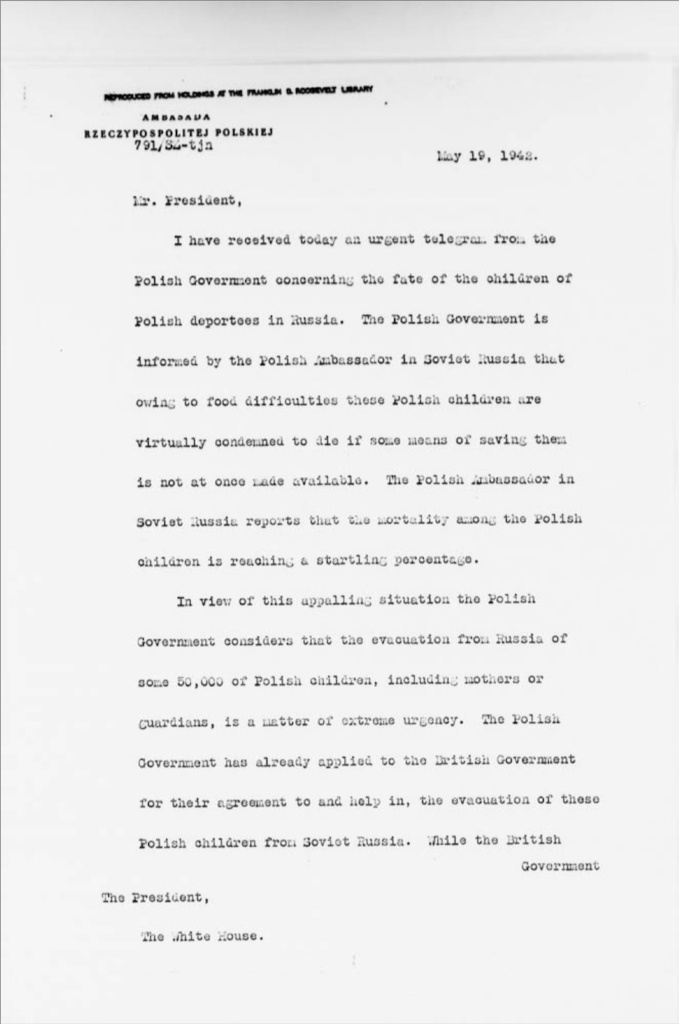

Sumner Welles and Jan Ciechanowski Memoranda, May 19, 1942

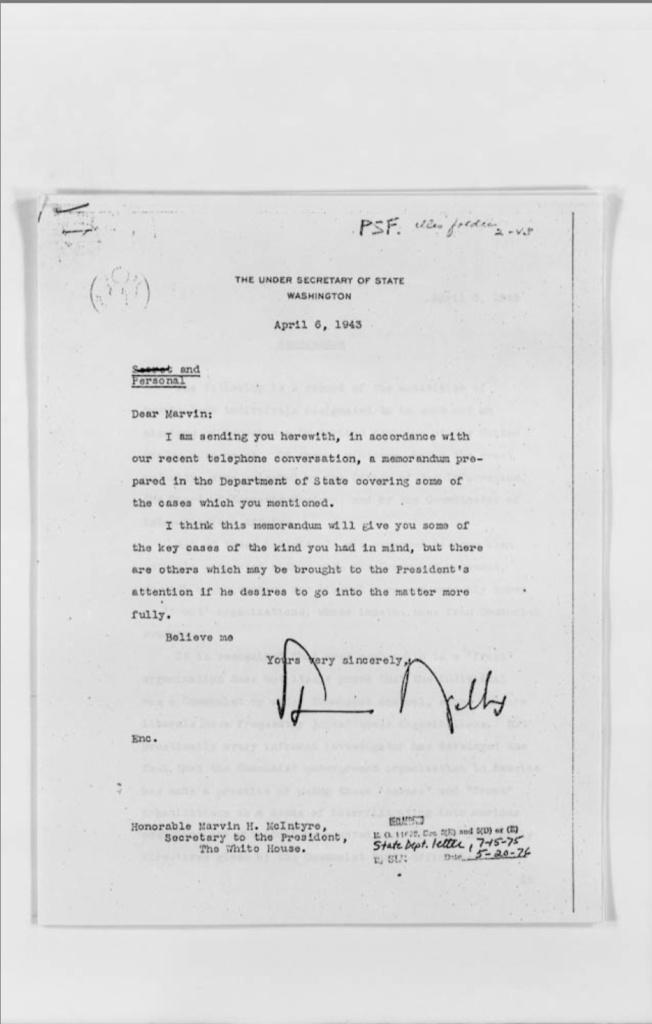

Sumner Welles Memoranda, April 5 and 6, 1943

Congressional Record–House, November 4, 1943

Notes

- Not all high-level officials in the Roosevelt administration were in favor of appeasing Stalin. A few progressive New Deal Democrats, including Roosevelt’s close friend and advisor Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, warned the White House about Soviet influence in the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) and its overseas radio division which produced what would later be called Voice of America (VOA) programs. Welles told the White House in April 1943 in a secret memo that the first VOA director John Houseman was hiring communists. The State Department, supported by the U.S. Army Intelligence, refused to issue a U.S. passport to Houseman for government travel abroad. Houseman was forced to resign. Welles’ complaint was not publicized. His memo to the White House remained classified for several decades. Sumner Welles also played a key role in arranging for getting Mexico to accept a group of Polish children refugees and for U.S. assistance for Polish refugees. See: Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psfb000259.pdf.

- The bipartisan Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, also known as the Madden Committee, said in its final report issued in December 1952: “In submitting this final report to the House of Representatives, this committee has come to the conclusion that in those fateful days nearing the end of the Second World War there unfortunately existed in high governmental and military circles a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Soviet Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis.” The committee added: “For reasons less clear to this committee, this psychosis continued even after the conclusion of the war. Most of the witnesses testified that had they known then what they now know about Soviet Russia, they probably would not have pursued the course they did. It is undoubtedly true that hindsight is much easier to follow than foresight, but it is equally true that much of the material which this committee unearthed was or could have been available to those responsible for our foreign policy as early as 1942.” The Madden Committee also said in its final report in 1952: “This committee believes that if the Voice of America is to justify its existence, it must utilize material made available more forcefully and effectively.” A major change in VOA programs occurred, with much more reporting being done on the investigation into the Katyń massacre and other Soviet atrocities, but later some of the censorship returned. Radio Free Europe (RFE), also funded and indirectly managed by the U.S., never resorted to such censorship, and provided full coverage of all communist human rights abuses. See: Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Final Report (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), 10-12. The report is posted on the National Archives website: https://archive.org/details/KatynForestMassacreFinalReport.

- The 1948 Smith-Mundt Act passed by the U.S. Congress significantly restricted use of tax dollars to target Americans with news and political commentary produced by the U.S. government. Some of these restrictions were later lifted. The Smith-Mundt Modernization Act of 2012, which was contained within the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (section 1078 (a)) and signed by President Obama, amended the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act and subsequent legislation, allowing for materials produced by the State Department and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), which included the Voice America, to be made more easily available within the United States.

- “During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy. President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination.” See: Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279. Also see: Ted Lipien, “President Eisenhower condemned biased Voice of America officials and reporters,” Cold War Radio Museum, December 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/president-eisenhower-condemned-biased-voice-of-america-reporters/.

- In 1943, American labor federations, the AFL and CIO, dominated by members of the Democratic Party, broke their collaboration with the Voice of America in producing programs about American labor because VOA broadcasters were communists and the mainstream American labor organizations were opposed to communism. The controversy became public and was described on the floor of the House of Representatives on November 4, 1943 by Rep. Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-Massachusetts) who was later U.S. Ambassador to Canada. “MR. WIGGLESWORTH. I call as witness in this connection the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations. I refer specifically to an article appearing recently in the World-Telegram. The gentleman from New York [Mr FISH] put the article in the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD, and you will find it in the RECORD of Tuesday, October 12, 1943, I shall not reinsert it, but here is the original of that article. You will notice the headlines. The leading headline is ‘Unions label O. W. I. radio program communism.’ That article very briefly asserts that the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations made a joint protest over 10 months ago to Elmer Davis to the effect that the O. W. I. overseas branch had been regularly broadcasting Communist propaganda in its daily short-wave radio programs. It states further that after months of futile negotiation the A. F. of L. and C. I. O. liquidated their labor short-wave bureau set up to collect nonfactual news to be turned over to O. W. I. as broadcast material.” Also see: Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/ and “President Eisenhower condemned biased Voice of America officials and reporters,” Cold War Radio Museum, December 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/president-eisenhower-condemned-biased-voice-of-america-reporters/.

- Amanda Bennett, “Trump’s ‘worldwide network’ is a great idea. But it already exists.” The Washington Post, November 27, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-worldwide-network-is-a-great-idea-but-it-already-exists/2018/11/27/79b320bc-f269-11e8-bc79-68604ed88993_story.html.

- W. Averell Harriman, Office of War Information Official Dispatch, Number 3146, September 5, 1944, U.S. National Archives.

- Czesław Straszewicz, “O Świcie,” Kultura, October, 1953, 61-62. I am indebted to Polish historian of the Voice of America’s Polish Service Jarosław Jędrzejczak for finding this reference to VOA’s wartime role.

- Office of War Information, Overseas Branch, News and Features Bureau, “Manual of Information.” Restricted. Prepared by Training Desk. February 1, 1944

- Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.), March 13 and 14, 1952, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), 455.

- Ted Lipien, “OWI head Elmer Davis spreads Soviet Katyn propaganda lie in Voice of America broadcasts,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 11, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/owi-head-elmer-davis-promotes-soviet-katyn-propaganda-lie-in-the-u.s.-and-in-voice-of-america-radio-broadcasts/. Elmer Davis broadcast in support of the Soviet Katyń lie can also be heard at http://www.wnyc.org/story/tunisia-poland/.

- Office of War Information (OWI), January 31, 1943, “Japanese Relocation,” C-SPAN, https://www.c-span.org/video/?323978-1/japanese-relocation

- Eighty-Second Congress, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, 455.

- July 8, 1942 confidential letter from Helena Sikorska to Eleanor Roosevelt with attached letters from wives of missing Polish prisoners in the Soviet Union.

- Sikorska, Helena. The Dark Side of the Moon, preface by T. S. Eliot. London: Farber and Farber, 1946.

- Marek Walicki who had escaped from Poland 1949 and later worked as a journalist for Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America, where he was deputy director of VOA’s Polish Service, described the first days of the so-called “liberation” of Poland at the end of World War II. He was a young boy when the Red Army moved into the area near Warsaw. He wrote in his memoir, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (“From Peoples’ Poland to Radio Free Europe”) published in 2018 in Poland: “The Soviets finally came. On the first day of ‘liberation’ they raped in our area several women. Some were raped until they died.” See: Marek Walicki, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (Warsaw: Bellona, 2018), 55.

- See: Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, November 7, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/

- Eighty-Second Congress, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, 462. https://archive.org/details/katynforestmassa03unit/page/462.

- Eighty-Second Congress, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, 455.https://archive.org/details/katynforestmassa03unit/page/454.

- Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session On Investigation of The Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in The Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia; Part 3 (Chicago, Ill.), March 13 and 14, 1952, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Hearings Before The Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation on The Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), 455.

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.

- Paul Sturman, “Nowy Swiat,” Executive Office of the President, Office for Emergency Management Office Memorandum to Alan Cranston, July 3, 1943, Declassified. OWI-208-NC-148-E222-Box1077, U.S. National Archives.

- Paul Sturman, “Nowy Swiat and OWI releases,” Executive Office of the President, Office for Emergency Management Office Memorandum, January 4, 1944. Declassified. U.S. National Archives.

- Paul Sturman, “Nowy Swiat and OWI releases.”

- President’s Personal File 7543 – Sikorski, General Wladslaw, 1941-1942, Selected Digitized Documents Related to Refugees, Franklin D. Roosevelt Museum, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/hol/hol00117.pdf.

- Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013,http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psfb000259.pdf.

- See: Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psfb000259.pdf.

- Robert E. Sherwood, Director, Overseas Branch, Office of War Information; RG208, Director of Oversees Operations, Record Set of Policy Directives for Overseas Programs-1942-1945 (Entry363); Regional Directives, January 1943-October 1943; Box820; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

- Office of War Information propaganda booklet with texts of two speeches by U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace translated into Polish. The booklet is in possession of the author and can be seen upon request.

- Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psfb000259.pdf.

- Arthur Krock, “Congress Reaction Likely,” The New York Times, July 31, 1943.

- 89 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – House of Representatives: November 4, 1943, 9136, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1943-pt7/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1943-pt7-10-2.pdf

- Ted Lipien, “Stefan Arski: Agent of Communist Collusion at VOA,” Cold War Radio Museum, April 14, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stefan-arski-agent-of-communist-collusion-at-wwii-voice-of-america/.

- Marek Walicki, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (Warsaw: Bellona, 2018), 170-182.

- American journalist Eileen Egan, who was then a Catholic Relief Services (CRS) worker helping the Polish children, wrote, “As a sealed train had been in the beginning of the trek of agony that carried simple people across three, four and, in the end, all five continents, of the world, so also the train that brought them into León and Colonia Santa Rosa was, in effect, also a sealed train.” See: Eileen Egan, For Whom There Is No Room: Scenes from the Refugee World (New York: Paulist Press, 1995), 19.

- Holly Cowan Shullman, “The Voice of America, US Propaganda and the Holocaust: ‘I Would Have Remembered’,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television 17, no. 1 (March 1997): 91-103. Also see: Ted Lipien, “Soviet Propaganda Overshadowed the Holocaust on Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, March 27, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/why-wwii-voice-of-america-ignored-the-holocaust/.

- Piotr Piwowarczyk, Hacienda Santa Rosa: A Polish Refuge in Mexico, Cosmopolitan Review, January 15, 2012, http://cosmopolitanreview.com/hacienda-santa-rosa/.

- Teresa Sokołowska quoted in “Santa Rosa: A Polish Odyssey in the Rhythm of Mariachi,” CULTURE.PL, July 22, 2013, https://culture.pl/en/article/santa-rosa-a-polish-odyssey-in-the-rhythm-of-mariachi.

- “Happiness in California,” Time, November 15, 1943, 23.

11 Comments

Richard Lucas

Thank you for an excellent article – sad and shocking though it is – it is so important that this history is widely known.

I created the Wojtek the Soldier Bear Group here http://www.facebook.com/groups/wojtekthesoldierbear so that this history might reach children

and gave a talk about it at TEDxKrakow here https://youtu.be/y0mhEnSL6Gw

greetings from Krakow, Poland

Richard

Comments are closed.