In 1943 nearly 1,500 Polish refugees, many of them children, including orphans, stopped briefly in the United States on their way to their refugee camp in Mexico, called Santa Rosa. Most Americans, however, never learned the true story of these homeless people who had been earlier Stalin’s prisoners while their parents and even some of the older children worked as slave laborers. To confuse Americans and to prevent the press from asking uncomfortable questions, Roosevelt administration propagandists put out a lie that the children and their caregivers were fleeing from the Nazis while at the same time officials were trying to limit access to the Polish refugees—all in an effort to maintain a friendly attitude among Americans toward Soviet Russia. The refugee children, many of whom lost their parents in the Soviet Union were a living proof that Stalin was a brutal dictator and a mass murderer. They had to be prevented from telling their story.

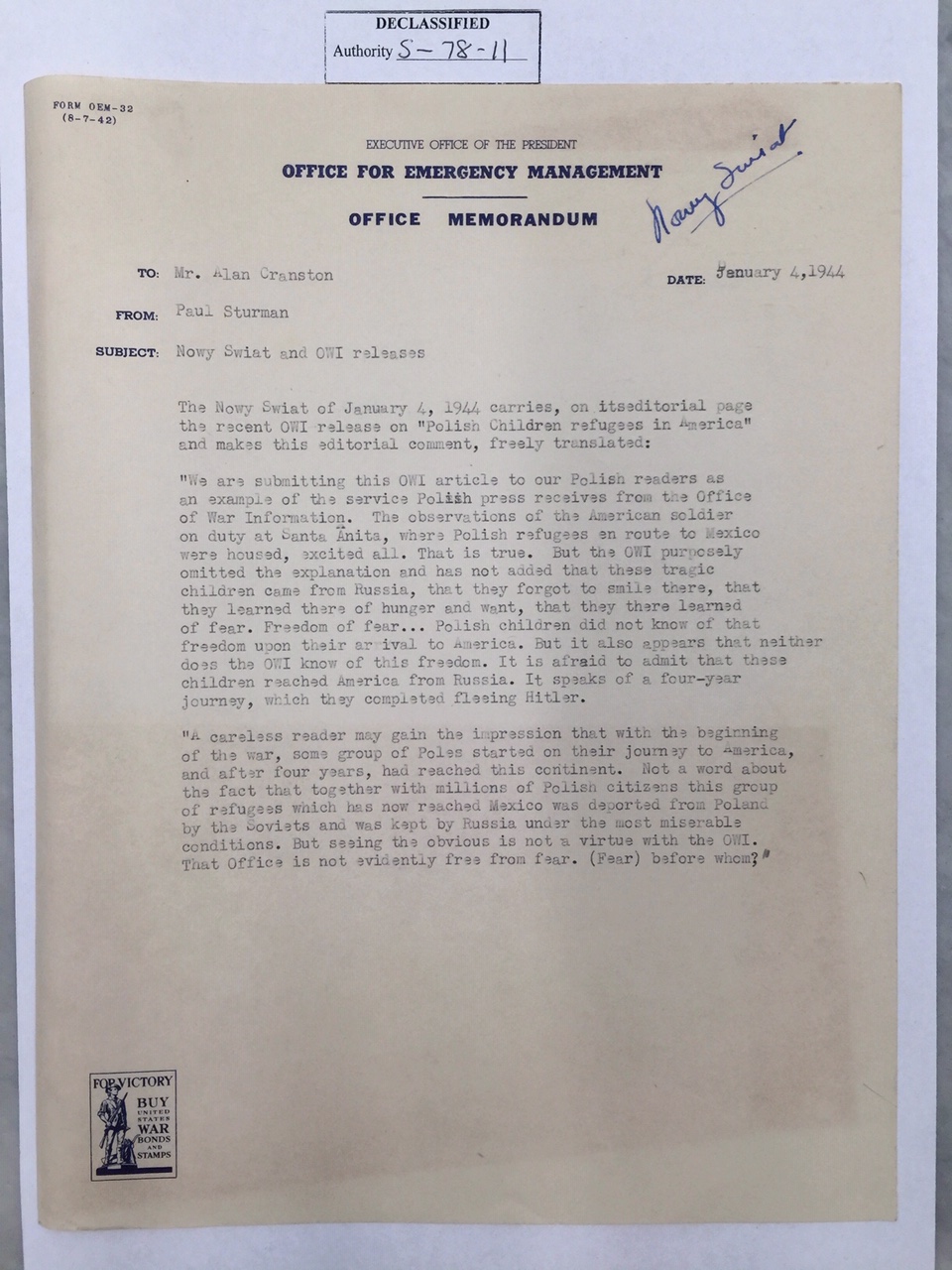

A previously classified U.S. government World War II document, now in the National Archives, offers a rare glimpse into how the wartime propaganda agency, the Office of War Information (OWI), which was in charge of both domestic and foreign U.S. government propaganda including Voice of America (VOA) radio broadcasts to Germany, Japan, Poland and other countries, tried to deceive American and foreign audiences about the Polish refugee children from Russia in order to protect Stalin’s reputation and America’s alliance with the Soviet Union. By then, Russia was admittedly the most important U.S. military ally against Nazi Germany, but only after Hitler broke his previous pact with Stalin and attacked the Soviet Union in 1941. The children who came from the eastern part of Poland occupied by the Red Army in 1939 were not victims of Hitler’s Fascism; they were victims of Stalin’s totalitarian Communism. They never saw any Germans occupiers. As the Polish American newspaper Nowy Świat pointed out in January 1944, they were arrested with their parents by the Soviets and sent to the Soviet Gulag.

The OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear.

A careless reader may gain the impression that with the beginning of the war, some group of Poles started on their journey to America, and after four years, had reached this continent. Not a word about the fact that together with millions of Polish citizens this group of refugees which has now reached Mexico was deported from Poland by the Soviets and was kept by Russia under the most miserable conditions. But seeing the obvious is not a virtue with the OWI. That Office is not evidently free from fear. (Fear) before whom?

In its January 4, 1944 editorial, Nowy Świat (“New World”), correctly assessed U.S. government’s propaganda. The U.S. government press release included a kernel of truth, but it was otherwise designed to deceive.

Voice of America broadcasters almost certainly did not tell the story of Czesław (Chester) Sawko “whose grim memory included carrying his little brother’s body to a makeshift morgue at a [Russian] railway station,” or the story another child refugee, Stanisława Synowiec (Stella Tobis), who “saw her mother for the last time when her train in Russia left without warning after her mother had got off in search of food.” She never saw her mother again. Czesław Sawko and Stanisława Synowiec both made it to Hacienda Santa Rosa. Only after the war they were able to resettle in the United States. Eventually they learned that while the Roosevelt administration did not want them in the United States, it was not how most Americans would have reacted had they known all the facts and were not lied to by U.S. government propagandists.

The first transport of 706 Polish refugees, including 166 children, aboard the USS Hermitage reached the San Pedro naval dock near Los Angeles on June 25, 1943. The women and children under 14 years of age were placed in the Griffith Park Internment Camp in Burbank and the men in the Alien Camp in Tuna Canyon. The second group of 726 Polish refugees including 408 children, mostly orphans arrived on the USS Hermitage in the fall of 1943 and was placed in the Santa Anita former detention camp for Japanese Americans. It was the second group that was mentioned in the misleading press release from the Office of War Information.

Out of 37,272 civilians who were Polish citizens evacuated from Russia to Iran in 1942, 13,948 were children. 1,434, most of them children, eventually arrived in Mexico.

To get to Mexico, the Polish children had to be transported from India on a U.S. Navy ship to a U.S. port. Their transport and support were negotiated between the Polish government in exile, represented in Washington by Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski, and the Roosevelt administration.

Many of the children were orphans. Some were accompanied only by their mothers. Fathers of some of the children had been either executed or died as prisoners in the Soviet Union. Some lost their mothers. Some still had fathers, but they were fighting the Germans as soldiers in the Polish Army in exile under the command of General Władysław Anders.

The children and their Polish adult caregivers, also former prisoners in Russia, were told by Polish and American government representatives that they were going to Mexico with a brief stopover on the west coast of the United States, but their reception after their arrival in southern California was much different from what they had expected. As one of the surviving children said years later, finding themselves being put on U.S. Army trucks, transported to a detention center and being kept behind a barbed wire fence guarded by American soldiers with rifles compounded the trauma of their recent imprisonment in Soviet Russia. They barely managed to leave the country which had arrested their parents and deported them from their homes in eastern Poland. They were hoping to taste full freedom in America, which they idealized. They found that they were not allowed to walk free and visit or interact with the people in the country of their dreams with the exception of some camp personnel and a few representatives of relief organizations. Most of them did not see the United States again until a few years after the war.

Before their arrival in a port in California on U.S. Navy ship Hermitage, they endured unbelievable suffering and completed a long journey that took them from Russia to Iran, from there to India, and finally to Los Angeles. Compared to the horrific conditions they had endured in Russia, these Polish children were treated with compassion and kindness by U.S. Army officers, soldiers, doctors, nurses, priests, nuns and other Americans with whom they came in contact. They were not completely abandoned and without help.

Initially, the Polish Army under the command of General Anders, which later fought against German armies alongside American and British forces, took care of them in Russia after their release and evacuated them to Iran. The Anders Army and civilian representatives of the Polish government in exile in London, the British government, and the U.S. government arranged for humanitarian aid and medical care in Iran. Their ocean voyage from India was paid for and organized by the U.S. government. It should be noted for the sake of balance that it was much more than most World War II refugees could have hoped to receive from the Roosevelt administration. While President Roosevelt refused the request from the Polish government in exile to resettle the children in the United States, he did approve a $3 million U.S. assistance program to bring them to Mexico.

Transported In Sealed Trains To Mexico

After a few days spent in the detention center in California used previously for Japanese Americans, the children were transported in a comfortable but locked train to Mexico. As they rode through southern United States, they still remained under military guard. U.S. soldiers locked all train doors, blacked out all windows and had orders not to allow anyone to talk with the passengers. What American officials feared most was that the story of the Soviet Gulag labor camps would leak out and become widely known through media reports about what really happened to these children and their parents in Russia. Secondly, officials feared that any publicity might encourage others in Europe to seek refugee status in the United States. There was concern that some of the children or their Polish caregivers might try to escape and remain illegally in the United States. No such escape attempts were reported.

The Roosevelt administration rejected requests for American adoptions, which would have been the most obvious and most humane solution to the problem of parentless Polish children. Officials would not allow these very young refugees from the Gulag to be placed with Polish American families. The U.S. government wanted to keep them isolated and to get them out of the country as soon as possible in case their continued stay and any media publicity could result in turning American public opinion against Soviet dictator Josef Stalin. Only when the American train they were on had reached the U.S.-Mexican border in Texas, the rifle-carrying U.S. guards disappeared. One of the children said later that at that moment they finally had experienced full freedom. Their lack of knowledge of Spanish prevented them from talking with the many Mexicans who came out to greet them, but they were finally free to speak to anyone they wanted. The warm welcome they had received in Mexico made a lasting impression. Those among them who are still alive continue to speak of their deep love and affection for Mexico. They continue to express their gratitude to the Mexican people for allowing them to stay in their country when they needed help and a safe place to live.

Victims Of Hitler Or Stalin?

Since the news of the children’s earlier arrival in the United States could not be completely hidden from the Polish American media, to confuse other Americans as well as foreign audiences listening to shortwave radio broadcasts of the Voice of America, propagandists in the FDR administration tried to portray these young refugees as fleeing from Nazi-occupied Poland rather than from the Soviet Union. Pro-Soviet officials in charge of U.S. propaganda did not want American and foreign radio listeners to learn about any communist atrocities. They feared that such negative publicity could undermine public support for the U.S.-Russia anti-Hitler alliance, or might even force Stalin to seek a truce and another pact with Hitler. While these fears were unfounded (a bipartisan congressional committee referred to them as “a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis.”), Hitler and Stalin were in fact war allies from August 1939 until June 1941. In 1939, Soviet Russia invaded and occupied the eastern part of Poland, annexed the Baltic States, and attacked Finland. In 1940 the Red Army occupied Romanian Bessarabia. The Soviets removed from their homes, imprisoned and forcefully deported in cattle train cars under most inhuman conditions millions of Poles and people of many other nationalities: Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Belorussians, Ukrainians, Tatars, Jews and many others. Many were arrested and executed. Others died during the deportations or later from harsh treatment, hard forced labor, starvation and illness. Only very few of the survivors managed to leave the Soviet Union during the war. They needed to be resettled in safe areas along with many other refugees who were fleeing countries occupied by Nazi Germany in east-central, southern and western Europe. Most of the Polish children who had escaped from Soviet Russia ended up in the British colonies in Africa, in India, and in New Zealand which accepted 700 children.

Soviet propaganda at times presented Polish refugees from Russia as being saved by Stalin, while American propaganda portrayed them as fleeing from the Nazis. There were many refugees fleeing the Nazi rule, but these Polish children were not chased out of their homes and imprisoned by the Gestapo. They lived in the part of Poland occupied in 1939 by the Red Army and they were prisoners in the Soviet Union. Polish American newspapers and better informed mainstream press tried to make these distinctions clear, while Soviet and U.S. government propagandists did everything possible to mislead and confuse Americans and foreign audiences about the nature of the Stalinist regime, presenting it as pro-democratic and progressive.

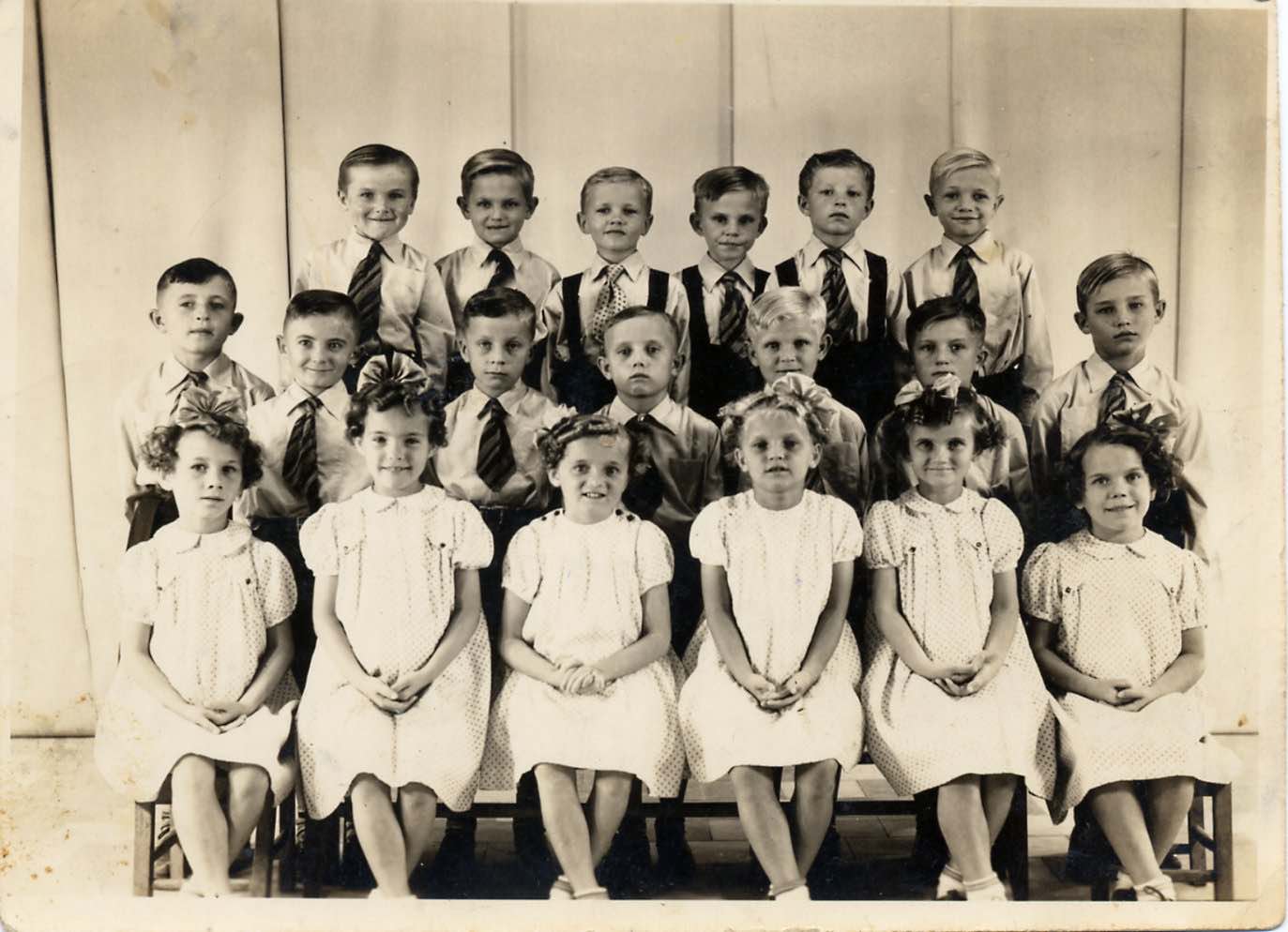

Photo Credit

- From Plowy Family Album. Courtesy of Julian Plowy, a former Santa Rosa Polish refugee child.